Difference between revisions of "Instruction:B5d9d0c7-579f-4415-ba3a-dc65836710bb"

(Undo revision 12125 by 0000-0003-4416-1351 (talk)) Tag: Undo |

|||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

In this module you will be asked to think about how knowledge is created, to reflect upon your own beliefs, assumptions and biases, and how these might impact upon research and ethics. | In this module you will be asked to think about how knowledge is created, to reflect upon your own beliefs, assumptions and biases, and how these might impact upon research and ethics. | ||

| − | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P- | + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-119 |

}} | }} | ||

{{Instruction Step Trainee | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

These questions represent two different kinds of knowledge: '''a priori''' and '''a posteriori'''. To answer questions A. and C., one can employ reasoning, whereas the answers to questions B. and D. stem from observation and experience. | These questions represent two different kinds of knowledge: '''a priori''' and '''a posteriori'''. To answer questions A. and C., one can employ reasoning, whereas the answers to questions B. and D. stem from observation and experience. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-120 | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Instruction Step Trainee | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| Line 54: | Line 55: | ||

Understanding how we construct knowledge helps us to take a critical standpoint and to exercise caution when making assumptions about proof. As well as the above evidence-proof issue, it is also important to acknowledge the impact of the researcher on the creation of knowledge. | Understanding how we construct knowledge helps us to take a critical standpoint and to exercise caution when making assumptions about proof. As well as the above evidence-proof issue, it is also important to acknowledge the impact of the researcher on the creation of knowledge. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-124 | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Instruction Step Trainee | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| Line 63: | Line 65: | ||

| − | + | *The sense perception of the observer | |

| − | * The sense perception of the observer | + | *The impacts of the observer |

| − | * The impacts of the observer | + | *The viewpoint of the observer |

| − | * The viewpoint of the observer | + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-128 |

}} | }} | ||

{{Instruction Step Trainee | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| Line 76: | Line 78: | ||

{{{!}} class="wikitable" | {{{!}} class="wikitable" | ||

| − | {{!}}[[File:Swirl.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless{{!}}300x300px]] | + | {{!}}[[File:Swirl.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless{{!}}300x300px|link=Special:FilePath/Swirl.pngcenterframeless300x300px]] |

| − | {{!}}[[File:Man leaning.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless{{!}}300x300px]] | + | {{!}}[[File:Man leaning.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless{{!}}300x300px|link=Special:FilePath/Man_leaning.pngcenterframeless300x300px]] |

{{!}}- | {{!}}- | ||

| − | {{!}}[[File:Bird in the hand.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless]] | + | {{!}}[[File:Bird in the hand.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless|link=Special:FilePath/Bird_in_the_hand.pngcenterframeless]] |

| − | {{!}}[[File:Rabbit duck.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless]] | + | {{!}}[[File:Rabbit duck.png{{!}}center{{!}}frameless|link=Special:FilePath/Rabbit_duck.pngcenterframeless]] |

{{!}}} | {{!}}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

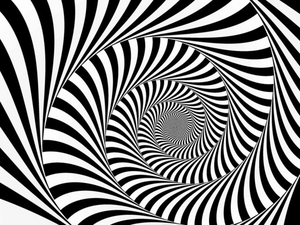

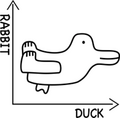

How we interpret the information from our senses to have meaning is termed ‘perception’. Two people might be exposed to the same sensory experience, but the way in which they interpret the information can differ. Perception of the same senses can vary from one person to another because each person interprets stimuli differently based on their learning, memory, emotions, and expectations. For instance, if we ask five people to describe a painting, it is likely that the five descriptions will be different, even though the people are all looking at the same painting. | How we interpret the information from our senses to have meaning is termed ‘perception’. Two people might be exposed to the same sensory experience, but the way in which they interpret the information can differ. Perception of the same senses can vary from one person to another because each person interprets stimuli differently based on their learning, memory, emotions, and expectations. For instance, if we ask five people to describe a painting, it is likely that the five descriptions will be different, even though the people are all looking at the same painting. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 5 Audio Transcript 1 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Impacts Of The Observer | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:A drop of water.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Researchers in many fields have long known that the act of looking at something can change it. This holds true for people, for animals, and for particles. Below you will see four well known examples of how an observer can have an impact on what they are observing. For this drag and drop exercise, match the impact type to the meaning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Exercise Feedback''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | These phenomena are well known in research. For instance, being observed makes psychiatric patients a third less likely to require sedation (Damsa et al, 2006), or the famous double slit experiment in modern physics. But many people believe that what we see is never what ‘really is’, even in the most highly controlled experimental settings. What do you think? | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 5 Audio Transcript 1 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=The Viewpoint Of The Observer | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:A spyglass.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Sometimes its not just the presence but the viewpoint which changes the interaction with the observed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The third influencing factor upon what is observed stems from the viewpoint of the observer. Researchers are not neutral processors of information. As human beings, they bring with them a host of assumptions and preconceptions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Observation is dependent upon and coloured by our individual senses and our background beliefs and assumptions. In research, many of our background beliefs and assumptions are associated with the paradigm in which we operate, as we consider next. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-133 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Scientific Paradigms | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Glass and iron lattice.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Video Transcript''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The concept of scientific paradigms was introduced by Thomas Kuhn in 1962 in the book: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. By ‘scientific revolution’ Kuhn has in mind a major turning point in the development of science, such as is associated with Copernicus, Newton, or Einstein. Each of these figures initiated a spectacular change of course in the development of science, which is often characterised as a revolutionary change.<div> | ||

| + | According to Kuhn, a scientific revolution is not so much a leap forward as a change of direction. When a scientific revolution occurs, science does not progress more rapidly along a pre-determined path, but rather sets out along a different path altogether. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Researchers who share a paradigm will also share certain basic beliefs; they share a particular understanding of what science is all about, and how it can be pursued. In essence, they share a way of seeing the world. Once there is convergence on a paradigm, there is a framework in which problems can be solved, researchers in the field have a clear idea of where the problems lie, and of what might count as a solution to them. The researchers speak a common language. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-137 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=What Is A Paradigm? | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Glass and iron lattice 2.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Since Kuhn, use of the word ‘paradigm’ has been broadened and nowadays people apply it in many different settings, but these are the key lessons. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-138 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=A View From Somewhere | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Man overlooking view.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Kuhn suggested that all scientific knowledge is ‘situated’ knowledge and cannot represent a ‘view from nowhere’. We all view the world from within a particular set of social and epistemic practices. According to Kuhn, scientists working within different paradigms are effectively working in different worlds. But how do we know which paradigm we are working in? | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-140 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Which Paradigm Are You Working In? | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:A view of mountains high up on a hill.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Which paradigm are you working in? Look at the descriptions on the end points of each question, and try to work out where you and your research project might fall along each continuum. Are you more of a realist or more of a relativist? Is your approach to knowledge generation more positivist or interpretivist? Do these aspects fit with the methodological stance that you take in your research? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Most people operate somewhere between the extremes. Additionally, it is possible to alter one’s positionality in response to different contexts. For instance, when addressing a research question which requires broad statistics, one might take a more positivist stance; when in-depth inquiry of a qualitative nature is required, one might take a more interpretivist stance. The important point is that we are cognisant of our perspective and its influence upon the knowledge that we create. | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Interactive Content=Resource:H5P-143 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Identifying Personal Assumptions And Biases | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Wooden figures joined by lines.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the final part of this module, we consider how we might become more cognisant of our embedded beliefs and assumptions through critical reflection. This in turn can help us to take a critical approach to ethical analysis. To begin with, we ask you to undertake an exercise. | ||

| + | [[File:Chair.png|center|frameless|700x700px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Our understanding of the world may have as much to do with our minds as with the world. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Write a short description of the image above. What do you notice? What do you think has happened here? Where do you think it might be? Please note any other thoughts that come to mind in relation to the image. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Critical Reflection | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Man thinking.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Critical reflection is the process by which adults identify the assumptions governing their actions, locate the historical and cultural origins of the assumptions, question the meaning of the assumptions, and develop alternative ways of acting (Stein, 2000, p1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Now return to your description of the image above and reflect on the following questions: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * What assumptions are implicit in my account and where do they come from? | ||

| + | * What does my account imply about my basic ideals or values and my personal emotional, social, cultural, historical, or political assumptions? | ||

| + | * What might be the perspective of others and how/why is mine different? | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Activity Feedback | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Influence text.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Describing an image may seem like a simple cognitive activity. However, our impressions of an image or any other resource are influenced by a wide range of factors, including those listed by Fook (2006). Engaging in critical reflection through developing the habit of noticing our reactions, and recognising where they come, from will enable a greater awareness of our own assumptions. In the above activity, you have engaged with the first stage two components of critical reflection as described by Fook (2006). In the next section of the module, we explore a model to aid Fook’s second stage third and fourth components of re-evaluation and reworking of concepts and practice based on critical reflection and analysis. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Taking A Self-Aware And Critical Approach To The Analysis Of Ethics Issues | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Self awareness blocks.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | When considering complex ethics issues, critical analysis ensures that decisions are based upon well-founded information and sound arguments rather than speculation or faulty logic. This will include in-depth consideration of an issue from multiple perspectives. To be critical in this regard, means that one recognises and questions the basis of assertions, unfounded assumptions, flaws in logic, generalisations and so on. Additionally, when undertaking critical analysis, it is vital that one is mindful of potential sources of bias through engagement in critical reflection. | ||

| + | |||

| + | What might this look like in practise? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In this module we have introduced a lot of complex ideas. Of course, it’s not possible to gain an in-depth understanding from this brief introduction. It takes time to develop the appropriate skills for critical thinking in ethics. If you want to delve into the subject further, please see the recommendations on the ‘further resources’ page. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [https://classroom.eneri.eu/node/207 Next Page] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=End Of Module Quiz | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[File:Quiz blocks.png|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | You can try these questions to see whether your learning from this module addresses the intended learning outcomes. No one else will see your answers. No personal data is collected. | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Instruction Step Trainee | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Title=Module Evaluation | ||

| + | |Instruction Step Text=[[file:person_sat_at_computer_in_office.jpg|center|frameless|600x600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thank you for taking this irecs module! | ||

| + | |||

| + | Your feedback is very valuable to us and will help us to improve future training materials. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We would like to ask for your opinions: | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. To improve the irecs e-learning modules | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. For research purposes to evaluate the outcomes of the irecs project | ||

| + | |||

| + | To this end we have developed a short questionnaire, which will take from 5 to 10 minutes to answer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Your anonymity is guaranteed; you won’t be asked to share identifying information or any sensitive information. Data will be handled and stored securely and will only be used for the purposes detailed above. You can find the questionnaire by clicking on the link below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This link will take you to a new page; [https://eur01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fforms.office.com%2Fe%2FK5LH08FyvQ&data=05%7C02%7CKChatfield%40uclan.ac.uk%7Cde983f54bcc64d66a02908dcd0b50ccd%7Cebf69982036b4cc4b2027aeb194c5065%7C0%7C0%7C638614723283127814%7CUnknown%7CTWFpbGZsb3d8eyJWIjoiMC4wLjAwMDAiLCJQIjoiV2luMzIiLCJBTiI6Ik1haWwiLCJXVCI6Mn0%3D%7C0%7C%7C%7C&sdata=shLTj7qPsGmGj0JOoPRZV2LhKbl5XOOhAbo7F%2FWzW7s%3D&reserved=0 https://forms.office.com/e/K5LH08FyvQ] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thank you! | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Instruction Remarks Trainee}} | {{Instruction Remarks Trainee}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:48, 26 August 2025

Critical Thinking, Standpoint & Ethics

The aim

To encourage learners to reflect critically upon their own beliefs and assumptions and to recognise the importance of positionality in the construction of knowledge and approach to ethical analysis.

At the end of this module, learners will be able to:

- Reflect upon their own positionality, where it comes from, how it influences their thinking and personal biases.

- Critically examine the basis of knowledge.

- Appraise the significance of alternative epistemological positions.

- Take a critical approach to ethical analysis.

Module Introduction

Video Transcript

According to Burbules and Berk (1999): Where our beliefs remain unexamined, we are not free; we act without thinking about why we act, and thus do not exercise control over our own destinies (p46).

An understanding of where our knowledge, beliefs and assumptions come from, and how we are positioned in relation to our research is vital for an ethical approach to research and analysis. Cultivating a habit of critical reflection is an important step towards gaining this understanding.

In this module you will be asked to think about how knowledge is created, to reflect upon your own beliefs, assumptions and biases, and how these might impact upon research and ethics.

Thinking About Knowing

We begin with some questions to start you thinking about where your knowledge comes from. Do you know the answers to these questions?

(Complete the quiz before reading on)

Easy? Maybe, but how did you know the answers?

These questions represent two different kinds of knowledge: a priori and a posteriori. To answer questions A. and C., one can employ reasoning, whereas the answers to questions B. and D. stem from observation and experience.

Thinking about Knowing continued

Philosopher Immanuel Kant maintained that a priori knowledge is independent of experience. He contrasted this with a posteriori knowledge, which has its sources in experience and observation. In life, most knowledge is of the a posteriori form; it is rooted in experience and observation.

Watch this video to find out why philosophers think there might be a problem with this.

The Problem Of Induction

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 3 Audio Transcript 1

I Saw It With My Own Two Eyes

For most people, the ultimate proof that something is true is to see it for themselves. But how reliable are your observations? In the following pages, we will consider three potential influencing factors:

- The sense perception of the observer

- The impacts of the observer

- The viewpoint of the observer

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 4 Audio Transcript 1

The Sense Perception Of The Observer

We receive information through one or more of the senses: sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste, but do we perceive things as they really are? Take a close look at the images below:

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 5 Audio Transcript 1

Impacts Of The Observer

Researchers in many fields have long known that the act of looking at something can change it. This holds true for people, for animals, and for particles. Below you will see four well known examples of how an observer can have an impact on what they are observing. For this drag and drop exercise, match the impact type to the meaning.

Exercise Feedback

These phenomena are well known in research. For instance, being observed makes psychiatric patients a third less likely to require sedation (Damsa et al, 2006), or the famous double slit experiment in modern physics. But many people believe that what we see is never what ‘really is’, even in the most highly controlled experimental settings. What do you think?irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 5 Audio Transcript 1

The Viewpoint Of The Observer

Sometimes its not just the presence but the viewpoint which changes the interaction with the observed.

The third influencing factor upon what is observed stems from the viewpoint of the observer. Researchers are not neutral processors of information. As human beings, they bring with them a host of assumptions and preconceptions.

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 7 Audio Transcript 1

Scientific Paradigms

Video Transcript

The concept of scientific paradigms was introduced by Thomas Kuhn in 1962 in the book: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. By ‘scientific revolution’ Kuhn has in mind a major turning point in the development of science, such as is associated with Copernicus, Newton, or Einstein. Each of these figures initiated a spectacular change of course in the development of science, which is often characterised as a revolutionary change.According to Kuhn, a scientific revolution is not so much a leap forward as a change of direction. When a scientific revolution occurs, science does not progress more rapidly along a pre-determined path, but rather sets out along a different path altogether.

Researchers who share a paradigm will also share certain basic beliefs; they share a particular understanding of what science is all about, and how it can be pursued. In essence, they share a way of seeing the world. Once there is convergence on a paradigm, there is a framework in which problems can be solved, researchers in the field have a clear idea of where the problems lie, and of what might count as a solution to them. The researchers speak a common language.

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 8 Video Transcript

What Is A Paradigm?

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 9 Audio Transcript 1

A View From Somewhere

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 10 Audio Transcript 1

Which Paradigm Are You Working In?

Which paradigm are you working in? Look at the descriptions on the end points of each question, and try to work out where you and your research project might fall along each continuum. Are you more of a realist or more of a relativist? Is your approach to knowledge generation more positivist or interpretivist? Do these aspects fit with the methodological stance that you take in your research?

irecs Critical thinking, standpoint & ethics step 11 audio transcript 1

Identifying Personal Assumptions And Biases

In the final part of this module, we consider how we might become more cognisant of our embedded beliefs and assumptions through critical reflection. This in turn can help us to take a critical approach to ethical analysis. To begin with, we ask you to undertake an exercise.

Our understanding of the world may have as much to do with our minds as with the world.

Critical Reflection

Critical reflection is the process by which adults identify the assumptions governing their actions, locate the historical and cultural origins of the assumptions, question the meaning of the assumptions, and develop alternative ways of acting (Stein, 2000, p1).

Now return to your description of the image above and reflect on the following questions:

- What assumptions are implicit in my account and where do they come from?

- What does my account imply about my basic ideals or values and my personal emotional, social, cultural, historical, or political assumptions?

- What might be the perspective of others and how/why is mine different?

Activity Feedback

Taking A Self-Aware And Critical Approach To The Analysis Of Ethics Issues

When considering complex ethics issues, critical analysis ensures that decisions are based upon well-founded information and sound arguments rather than speculation or faulty logic. This will include in-depth consideration of an issue from multiple perspectives. To be critical in this regard, means that one recognises and questions the basis of assertions, unfounded assumptions, flaws in logic, generalisations and so on. Additionally, when undertaking critical analysis, it is vital that one is mindful of potential sources of bias through engagement in critical reflection.

What might this look like in practise?

In this module we have introduced a lot of complex ideas. Of course, it’s not possible to gain an in-depth understanding from this brief introduction. It takes time to develop the appropriate skills for critical thinking in ethics. If you want to delve into the subject further, please see the recommendations on the ‘further resources’ page.

Module Evaluation

Thank you for taking this irecs module!

Your feedback is very valuable to us and will help us to improve future training materials.

We would like to ask for your opinions:

1. To improve the irecs e-learning modules

2. For research purposes to evaluate the outcomes of the irecs project

To this end we have developed a short questionnaire, which will take from 5 to 10 minutes to answer.

Your anonymity is guaranteed; you won’t be asked to share identifying information or any sensitive information. Data will be handled and stored securely and will only be used for the purposes detailed above. You can find the questionnaire by clicking on the link below.

This link will take you to a new page; https://forms.office.com/e/K5LH08FyvQ

Thank you!