Introduction to the evaluation of the effectiveness of Research Ethics and Integrity (REI) training

Introduction to the evaluation of the effectiveness of Research Ethics and Integrity (REI) training

What is this about?

We may start with a simple question: why measure research ethics and integrity (REI) training effectiveness? To teachers this may sound like a strange question as this is one of the main things teachers need to do – making a conclusion if the learners are learning, improving, developing. Watts et al. (2017) also highlight that occasionally various authorities require evidence of people improving their knowledge and skills as a result of a training.

Measuring the effectiveness of training is like conducting research – there should be a guiding question (e.g. What do participants learn, and how is that related to what they are meant to learn through the training? How do learning activities encourage engagement and learning?), then there should be a tool to collect information and a means to analyse the information. Finally, results should be interpreted, and one can make a conclusion about whether the training achieves its aims.

The BEYOND Measurement toolbox introduced in this module gives an overview of large-scale as well as small-scale feasible measurement instruments on short, medium and long-term training effects adapted to the needs of a variety of target groups and different fields/domains. We understand the measurement of training effect through the learning achieved and displayed as a result of participation in training. This means that the learning is always relative to the goals of the training. The examples of how to understand the learning taking place in REI training may be good for certain types of training and contexts, whereas in others they may not be feasible. Because training, its learning objectives and the pedagogical approaches vary, we have aimed to present a broad array of measurements and other means of evaluating the learning that takes place.

Why is this important?

Understanding Current Knowledge on Measuring Training Effectiveness

What do we know about measuring training effectiveness?

Self-assessment is one of the most prevalent means to measure effectiveness of REI training. The second most frequently used method for assessing training effect was a moral reasoning test. While the developed tools were mostly used pre and post intervention (with/without control groups) and the results were compared, there were other measures added to evaluate the learning process or student progress.

It also seemed that the tests designed for ethics training (like DIT, DEST, TESS) cannot be universally implemented to all REI training due to very different formats of training and/or availability of tests. There are also qualitative possibilities (like learning diaries, tasks submitted during other courses, etc.) to monitor the learning progress, and through that assess the effectiveness of training.

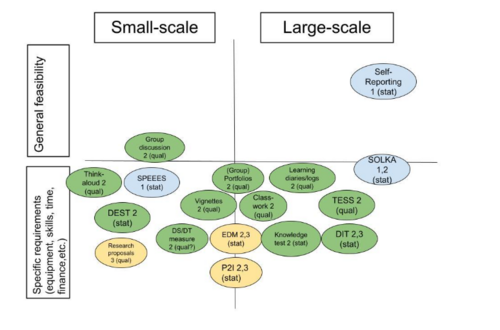

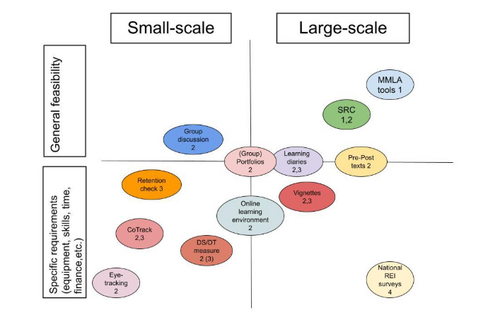

See figure 1 outlining the identified measures and their application scale and feasibility (more details in D4.1):

Figure 1. Measurement tools identified in the literature review (numbers indicate Kirkpatrick’s levels, see below) (tool descriptions in D4.1).

As can be seen in figure 1, self-reporting (blue bubbles) is the most feasible measure and that can be implemented large-scale (mostly). It is no wonder that this is, based on the literature review, also the most used approach. Also, SPEEES and SOLKA tests utilise self-reporting.

Most tools measure the content or the learning process (green bubbles) – they give information about what was learned during the training. As indicated, feasibility of the measures is not high – either a lot of work needs to be put into implementing the tool, they are not openly available, or they may be field specific. Possibilities for measuring behaviour (yellow bubbles) are scarce.

Comparing results collected with various tools is almost impossible because they measure different aspects of training with different analysis instruments. It is not possible to determine whether qualitative (indicated as ’qual’) or quantitative (indicated as ‘stat’ in Fig 1) methods of analysis are more feasible. Feasibility depends on the combination of various aspects, such as accessibility to the tool, need of special equipment, and competence required.Recognising Challenges in Assessing Training Effectiveness

Challenges in assessing training effectiveness are that results are limited through extensive missing data, heterogeneity of trainings and evaluation tools, short interventions not allowing sufficient time to induce change or development, and small sample sizes. As the goals of trainings differ, different tests are used to measure those goals, making comparisons difficult. In addition, measurements take a lot of time and labour to assess and analyse, especially if the data are qualitative and learners receive feedback on their learning and development.

Considering the Systemic Nature of REI Training Effectiveness

REI training effectiveness should be approached as a system. While measuring reactions and knowledge (or learning process) is quite simple, it is also important to measure common practices and the environment (impact on the institutions). Training outcomes are influenced by many factors, not least the match between perceived needs and what the training offers, that is, the alignment between needs, intended learning outcomes, training objectives, and training implementation.

Getting familiar with the terminology used in the toolbox

Large-scale in our module means that the tool can be used with big groups. As many REI training formats take place with small groups, we also outline tools for use in those groups. The presented tools can be used with different target groups and in different fields within HE (higher education) context. All analysis tools are applicable in different disciplines.

Short-, mid- and long-term are relative concepts. By short-term training effects we understand the learning, which is displayed during and soon after training; by mid-term, training effects learning, which is displayed when the training has ended and usually pertains to the learning content and/or learning process. By long-term effects we understand the learning that is displayed months or even years after training. The longer the timeframe is, the more challenging it becomes to pinpoint what is training effect and what is development and learning in a more general sense. Long-term effects are, thus, best approached as manifestations of behaviour over time.

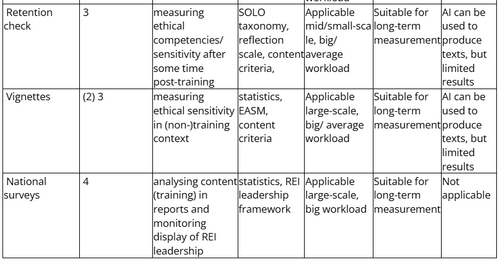

Summary of Tools Described

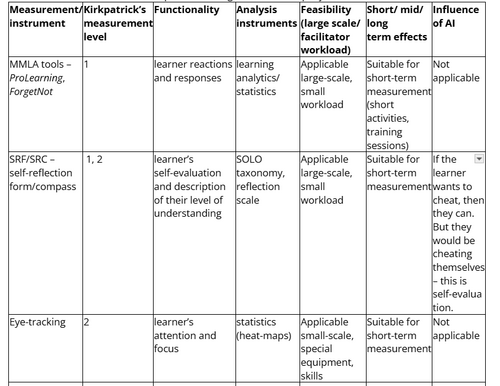

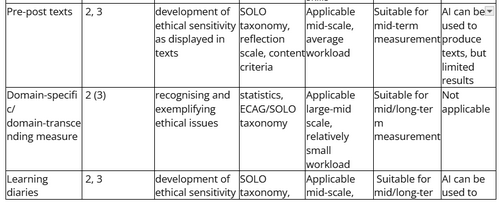

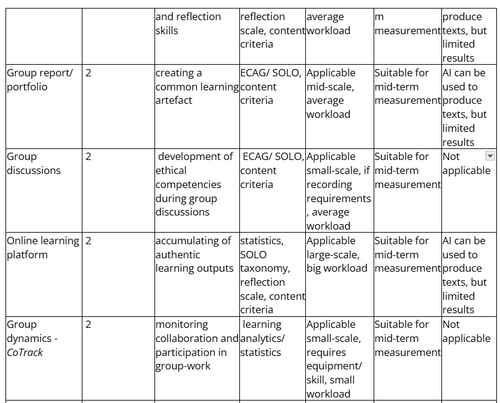

The table below outlines all the tools and provides evaluations of their functionality, feasibility, scale, term of effect as well as the potential impact of AI for their use. It is important to consider whether the measurement is vulnerable to unintended/undesirable use of AI especially in those cases when authentic learning tasks are utilised as indicators of training effect. There may also be cases in which AI use is neutral or even recommended along with instructions to learners to be mindful of the challenges with AI-created content and using any such content critically.

The table includes an assessment of appropriate level of training effectiveness (according to Praslova 2010/Kirkpatrick 1959), functionality, suggested instruments of analysis, feasibility, temporal dimension and potential manipulativeness by AI.

Reflecting on the toolbox and its possible use

We realise that this is not a conclusive list, just a toolbox collected for trainers. Still, we have tried to collect measurement tools to evaluate effectiveness on different levels – from self-reactions, to learning content and process, to common practices/behaviour, and to see the wider impact on the research community. All the included tools and analysis instruments have been tested in the REI training context.

At best, tools for measuring and assessing REI learning also serve a pedagogical function, that is, its use is part of the teaching activity and the learning process. The choice of the measure of effectiveness depends on the training format, learning objectives, pedagogical approach, learning activities, time available for its use, facilitators’ competencies and others. Depending on these criteria a measurement tool can be chosen, different tools scan be combined. It should also be remembered that no one size fits all – facilitators should familiarise themselves with different tools and analysis instruments and combine the ones they consider feasible. In addition, large-scale tools can be used also in case of small groups, but vice versa may not be possible.

Figure 2 outlines a map of tools based on feasibility and scale of use. Table 1 (see step 5) provides general information about the data collection and analysis tools.

Figure 2. Map of tools to measure REI training effectiveness.

To measure short-term training effects (meaning what is just happening and what the learners’ reactions are, during and right after the learning process) you can use: MMLA tools collecting learner reactions (e.g. ProLearning, ForgetNot), and Self-Reflection Form/Compass.

For mid-term training effects (information about the content and learning process) one can use: Eye-tracking, Pre and post texts, Domain-specific, domain-transcending measure, Learning diaries/journals, Group reports/portfolios, Group discussions, Monitoring the online learning environment, group-dynamics with CoTrack.

Long-term effects can be measured with (effects after the intervention, behaviour and practices): National REI barometers /surveys (consequently the national guidelines can be improved), Retention check - learner’s activities after the training (e.g. monitoring the ethics sections of articles or asking learners to do another task several months after the training to measure retention); implement vignettes in surveys/non-training contexts to measure ethical sensitivity of learners.

We also outline recommendations for the implementation of the tools and analysis instruments:

- Effectiveness of the training starts from careful planning – the alignment of learning outcomes, training content and evaluation is crucial. Analysis instruments could be considered when outlining the learning outcomes and content.

- The measurement tools could be used as pedagogical instruments – e.g. learning diaries can be used as a tool to support the development of learner’s reflection skills as well as measuring if those skills advance.

- Using similar analysis instruments provide an opportunity to compare the results of different training formats (e.g. the SOLO taxonomy).

- Combining various measurement tools (triangulation) provides a holistic picture of the entire learning process as well as outcomes (i.e. effect). Using different measurement tools at various measurement points provides an alternative angle to triangulation.

- Measurement on level 4 should be implemented on a national (perhaps also institutional) level.

- An implementation example: to measure participants’ reactions during or right after the training, Self-Reflection Form can be used. In addition, if learners worked in groups their group discussions can be monitored, and if they provided a group-report or pre- and post-texts, the learning process can be evaluated based on the SOLO taxonomy to measure the levels of understanding. Moreover, if possible, a couple of months after the training an additional case study could be given to the same learners, and the content of their analysis could again be evaluated with the SOLO taxonomy. This kind of effectiveness measure would give a possibility to triangulate the measurement in different time points. Analysing vignettes and participating in national REI surveys would provide insights on the wider research community.

Remarks

Authors: Erika Löfström, Anu Tammeleht, Simo Kyllönen,

This course was produced on behalf of the BEYOND project. The BEYOND project was finded by the European Union uder the grat agreement n. 101094714