Micromodule care ethics and environmental ethics

Micromodule care ethics and environmental ethics

By the end of this micromodule participants should be able to:

1) Understand core ethics of care concepts and their basis in feminist and indigenous philosophies

2) Identify care-based practices in your own research setting

3) Propose strategies for strengthening care-based and environmentally aware practices in your own research and research setting.Learn about care ethics

Watch this short video introducing ethics of care (or care ethics). Video

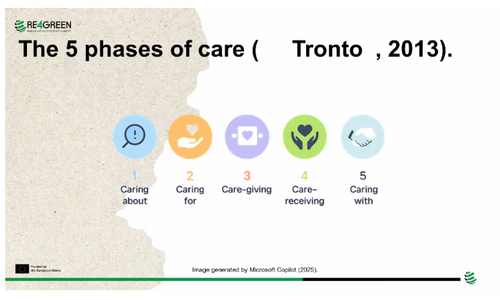

Reflect about the 5 phases of care in your research

Look back at the 5 phases of care by Toronto and think about your research. How could you reflect on and integrate the 5 phases of care in your research? You can think about your

research design or a specific phase of your research.

For inspiration you can look at this article where a research group describes in detail how

they have integrate the and reflected upon the 5 phases of care in their research.

[1]Extending care responsibilities to the environment

As we learned in step 1 care ethics values interconnectedness, interdependence, and rejects the individualistic rational autonomy, typical of the colonial wester perspective.

This way of understanding human relationship and of centering care responsibilities at the core of human flourishing was brought forward by feminist scholars and lies at the core of many indigenous practices and knowledges, where the interdependence among being and the reciprocal responsibilities that connect humans, the natural environment, including water and other beings, is recognized.

The concept of “care” is integrated in the discourse and practices of indigenous environmental movements and provide important paradigms for caring as part of environmental ethics.

According to Whyte and Cuomo (2016) indigenous conceptions of care include:

1) the importance of one’s awareness of their own place within a web of different

connections (including humans, non-human beings and entities, and collectives (e.g., forests, seasonal cycles);

2) the understanding of moral connections as including relationships of interdependence that motivate reciprocal responsibilities;

3) the valorization of skills and virtues, such as the wisdom of grandparents and elders, attentiveness to the environment, and indigenous stewardship practices;

4) the will to restore people and communities wounded by injustices by rebuilding

relationships that can generate responsibilities pertinent to the environmental challenges such as biodiversity loss;

5) the conception of political autonomy as involving the protection of the right to serve as responsible stewards of lands and the environment.

These conceptions of care align with the idea that in indigenous knowledge, care

responsibilities extend to nature and the environment. This is exemplified by the concept of kinship (i.e. the bond that exists between members of a group, often a family, based on which relationships, social structures, rights, obligations, and expectations are determined) which in indigenous traditions extends to the place we live in, including nature, animals and the elements which sustain life. In this view, kinship, is not merely a status (defined belonging to a certain group) but an action, and in particular the reciprocal care that members of the kinship exercise for each other.

Watch the video below:Kelsey Leonard: Why lakes and rivers should have the same rights as humans

Reflect: Extending kinship relationships to Nature

Extending kinship relationships to Nature implies extending the concept of interdependency to the environment and as a consequence the responsibilities that humans have towards the environment. This perspective, rooted in ancestral scientific foundation, based on experimentation, observation and adaptation is deeply embedded in indigenous systems around the world, including Ubuntu among the Bantu and Xhosa peoples of Africa, Lokahi for Native Hawaiians, All my relations widely used by Tribal and Indigenous nations across Turtle Island and Tendrel of Tibetan Buddhism from Tibet, the Himalayas, and South Asia: it underlines how humans hold care responsibilities toward non-human relatives (Gauthier et al 2005).

This view is defined by Gauthier et al. as “Kincentric ecology”:

Box:

Kincentric ecology describes how humans live as kin with the Natural World. It is a way of seeing and engaging with the world that recognizes humans and Nature as a part of an extended ecological family that shares origin and ancestry. It recognizes relationships as layered and interdependent, thus fostering kinship that leads to sustainability and preservation of ecosystems (Gauthier et al 2005, p. 2).

Reflect:

What are the implications of extending the concept of interdependency to the environment from a care ethics perspective? How does embracing a kincentric ecology influence the application of care ethics approach to research

Listen and reflect: “Acts of Care in Microplastics Science”

Now that we have learned about care ethics and the way which in care has been conceptualized and enacted by indigenous environmental movements let’s look at a particular story brough to us by a microplastic researcher. In this story we hear few examples of how care-based and environmentally aware practices can be embedded in the context of research.

Listen to the podcast: “Acts of Care in Microplastics Science” -link-

The podcasts touches on themes relevant to environmental ethics of care in research practice. Let’s revise them:

1. Care as a Relational Practice

Care is something we do an active, intentional practice.

We “live with plastics” exploring relational aspects of care between humans and materials.

Caring for plastics involves responsibility (e.g., recycling, waste reduction).

Care is contextual — both affective and practical.

2. Positioning of Care Practices

Care practices are not solutions, but ethical acts in themselves.

Acts of care happen everywhere, even amid imperfection.

These moments offer “glimmers of hope” and reveal the complexity of our relationships with plastics.

2. Vulnerability and Inequality

Some groups are more vulnerable to environmental pollutants than others.

Ethical research must recognize and respond to these inequalities.

The podcast focuses on plastic pollutants consider: What conditions cause vulnerabilities and inequality in your work?

3. Interdisciplinarity

Collaboration across disciplines is essential to address complex problems.

Building alliances helps broaden understanding and improve care practices.

4. Authenticity: Scientists and Plastic Use

Scientists produce significant plastic waste.

Laboratories rely heavily on single-use plastics — creating ethical paradoxes in care and sustainability.

Sharing stories and reflections about these paradoxes is part of ethical engagement.

5. Storytelling and Ethics

Storytelling is a vital medium for communicating care in research.

Research can engage with and reflect on care through shared narratives and creative forms.

Reflect:

Can you think of at least three ways in which you could implement small scale care-based and environmentally aware practices in your research?

Is there anything you would need to be able to implement the practices you thought of in

response to the question above? For instance, would you need the support of your institution? How can you make sure these needs are met?References

Urban Walker, M. 1998. Moral Understandings. A Feminist Study in Ethics. New York: Routledge.

Tronto, J. 1993. Moral Boundaries. A Political Argument For an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

Noddings, N. 1982. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley: University of CA Press.

Gilligan, C. 1982. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Harvard University Press.

Woodly, D., R.H. Brown, M. Marin, S. Threadcraft, C.P. Harris, J. Syedullah, and M. Ticktin.

2021. “The Politics of Care.” Contemporary Political Theory 20 (4): 890–925.

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-021-00515-8.

Wrigley, K. 2025. Care-full climate justice organising. Environmental Sociology, 1–13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2025.2484479

Noddings, N. 2015. Care ethics and “caring” organizations. In: Engster D, Hamington M (eds) Care Ethics and Political Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 72–84.

Weil, S. 1977. Simone Weil Reader. New York: Moyer Bell.

Whyte, K. and C. J. Cuomo. 2016. “Ethics of Caring in Environmental Ethics: Indigenous

and Feminist Philosophies.” In S. M. Gardiner and A. Thompson (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics Oxford: Oxford Handbooks, 234–247.

Inguaggiato, G., Pallise Perello, C., Verdonk, P., Schoonmade, L., Andanda, P., van den

Hoven, M., & Evans, N. 2024. The experience of women researchers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Research Ethics, 20(4), 780- 811. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470161241231268

Tronto, J.C. (2013). Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice. New Yourk: NYU Press.

Gauthier P. E., Chungyalpa D, Goldman RI, Davidson RJ, Wilson-Mendenhall CD. 2025.

Mother Earth kinship: Centering Indigenous worldviews to address the Anthropocene and

rethink the ethics of human-to-nature connectedness. Curr Opin Psychol. Aug(64): 102042.

doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2025.102042. Epub 2025 Apr 11. PMID: 40288260.