Using Different Learning Taxonomies

Using Different Learning Taxonomies

What is this about?

Why is this important?

Learning is what the learner does, but it can be facilitated through what trainers do and through appropriate teaching activities.[1] The Taxonomy of Significant Learning (sometimes also referred as the Fink’s taxonomy) is not hierarchical in the same way as the other two, however, it builds on Blooms’ taxonomy by including a long-forgotten affective component into the discussion (namely caring).[2] It encourages to include into the learning outcomes the objectives foundational knowledge, application, integration, a human dimension, caring, and learning to acquire competencies, thus providing a holistic approach to learning.[2] However, since the existing material aligns with Bloom's and SOLO frameworks, this module will primarily describe these two to ensure coherence and consistency in training delivery. Nevertheless, we encourage trainers to also consider the more effective type of learning objectives proposed in the Taxonomy of Significant Learning.

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses (Revised and updated edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Use the Bloom’s taxonomy

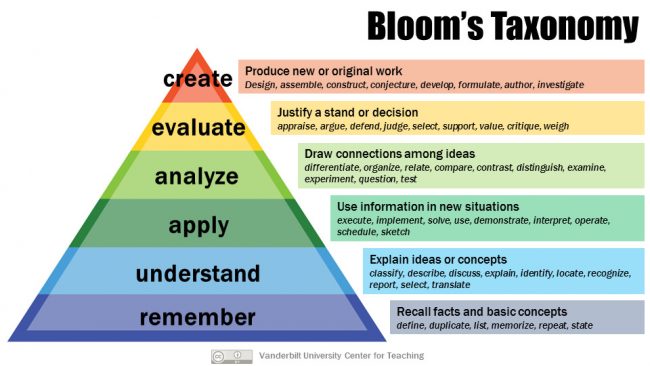

Bloom's Taxonomy is a well-known educational framework that offers a methodical way to classify learning objectives according to cognitive difficulty. (e.g., Adams, 2015).[1] It is a hierarchical framework that uses cognitive complexity to classify learning objectives. Benjamin Bloom created it in the 1950s, and it is now a vital instrument in educational theory and practice. The taxonomy is divided into six stages: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating, and creating. The levels are arranged from lower to higher order cognitive skills. Fundamentally, remembering entails recollecting words, information, and fundamental ideas. Understanding is more than just remembering concepts; it also involves understanding meanings. Applying necessitates applying knowledge to novel contexts or problem-solving. Analysing means dissecting data into its constituent elements and identifying connections between them. Making decisions based on standards and criteria is the process of evaluating. Creating, in the end, involves coming up with original concepts and/or interpretations. The goal of applying Bloom's Taxonomy to training aims and results is to enhance comprehension by considering the knowledge, skills, and competencies that the specific training programmes were created to impart. The Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analysing, Evaluating, and Creating domains of Bloom's Taxonomy each reflect a different cognitive process and the depth and complexity of learning.

All taxonomic levels are relevant irrespective of the study or career level. However, the taxonomic levels may mean different things for different individuals. For example, application of knowledge may mean engaging with research designs, but senior researchers often use more complex designs than students still learning how to do research. Nevertheless, it is essential that the learning extends beyond remembering and understanding, and that the complexity of activities at all levels gradually grow as the individual gains experience, knowledge and confidence.

· remembering and understanding: focus on memorizing key ethics concepts and theories. For example, students should master basic principles and terminology related to ethics and integrity.

· applying and analysing: engage in practical applications and critical thinking. Apply ethics concepts to real-life scenarios, such as conducting experiments and analyzing data.

· evaluating and creating: evaluate research findings and create new knowledge. Encourage learners to think critically and innovate in ethical dilemmas.

- ↑ Adams, N. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 103(3), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010

Use the SOLO taxonomy

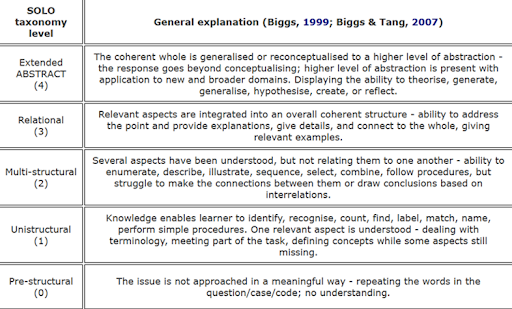

Besides using Bloom’s Taxonomy to define learning objectives, the SOLO Taxonomy can be used .[1][2] The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome, or SOLO, is a way to set the learning outcomes according to how complicated they are.[1][2] This allows us to evaluate students' work based on its quality following the idea of increasing understanding of complexities: Initially, we learn one or a few aspects of the task (unistructural), then multiple aspects that are unrelated to each other (multistructural), then we learn how to integrate them into a whole (relational), and lastly, we can generalise that whole to still-untaught applications (extended abstract). It evaluates the quality of students' work and understanding:

· pre-structural: identify basic ethical concepts without fully understanding them.

· unistructural: recognize and label simple ethical procedures.

· multistructural: enumerate and describe ethical principles but struggle to connect them.

· relational: analyze and apply ethical concepts, understanding interrelations.

· extended abstract: generalize and theorize ethical principles to solve novel dilemmas.

The SOLO taxonomy has been used to evaluate effectiveness of trainings as well as the development of ethical sensitivity and has been proven to be effective in the context of research ethics and integrity training.[3][4][5][6] The verbs emphasised in the descriptions below can be used as indicators of the appropriate levels in learning objectives.

Pre-structural level (0)

At the pre-structural level the learner fails to identify or approach topics in a meaningful way, but simply repeats the words in the question without understanding them.

Unistructural level (1)

At the unistructural level, the learner has sufficient knowledge to identify, recognise, count, find, label, match, name, and perform follow simple procedures. The learner identifies one relevant aspect displaying some familiarity with relevant concepts, but failing to outline multiple dimensions of it but failing to outline multiple dimensions of it. In the context of research ethics and integrity, this may mean identifying certain, perhaps common concepts, but having a limited view of them. For example, the learner may be able to identify some of the things that ought to be mentioned in an information letter to research participants but fails to understand all aspects of ensuring voluntary participation in research.

Multi-structural level (2)

At the multistructural level, the learner can enumerate, describe, illustrate, list, sequence, select, combine, and follow procedures, but struggles to make connections between concepts or draw conclusions based on interrelations. For example, the learner may understand that informed consent is necessary in research but fails to understand that this is so because of the need to respect people’s autonomy and right to make decisions that concern themselves.

Relational level (3)

At the relational level, the learner displays an ability to address the most relevant aspects of the concept and provide explanations pointing out interrelations and providing examples demonstrating their own reasoning. Corresponding action verbs include; analyse, apply, argue, compare, contrast, critique, explain causes, relate and justify. For example, the learner understands at least the main mechanisms and connections between FFP and the detrimental effects to science.

Extended abstract level (4)

At the extended abstract level, the coherent whole is generalised or re-conceptualised at a higher level of abstraction. The learner grasps a more abstract version of the concept, and recognises other domains to which the concept might be applied by displaying the ability to theorise, generate, generalise, hypothesise, create or reflect, formulate and reflect. For example, the learner is able to use knowledge about ethical analysis and ethical principles to solve a novel integrity-related dilemma, which the learner recognises is affecting a research group, but to which the learner has not been exposed before.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Using Constructive Alignment in Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning Teaching for Quality Learning at University (3rd ed., pp. 50-63). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- ↑ Löfström, E. (2012). Students’ ethical awareness and conceptions of Research Ethics. Ethics & Behavior, 22(5), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2012.679136

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., & Löfström, E. (2023). Learners’ self-assessment as a measure to evaluate the effectiveness of research ethics and integrity training: can we rely on self-reports? Ethics & Behavior, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2023.2266073

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., Löfström, E. & Rodríguez-Triana, M. J. (2022). Facilitating development of research ethics and integrity leadership competencies. International Journal of Educational Integrity, 18, 11, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-022-00102-3

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., Löfström, E., & Rajando, K. (Accepted 2024) Effectiveness of research ethics and integrity competence development – what do learning diaries tell us about learning? International Journal of Ethics Education.

Use The Taxonomy of Significant Learning

The taxonomy of Significant Learning or the Fink’s taxonomy is a non-hierarchical system that helps trainers devise learning outcomes to support deep learning. No dimension is considered more important than the other and within the course various aspects should be present.[1] Thus, this taxonomy provides an alternative frame for devising learning objectives for training.

· foundational knowledge: understand and recall ethical information.

· application: demonstrate skills in ethical analysis and problem-solving.

· integration: connect ethical theories and compare different approaches.

· human dimension: recognize the impact of ethical decisions on oneself and others.

· caring: develop empathy and values related to ethics.

· learning to learn: reflect on the learning process and self-assess ethical understanding.- ↑ Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses (Revised and updated edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Apply and Compare the Taxonomies

To illustrate how the taxonomies can be applied in creating learning objectives for training, we provide an example of an analysis of learning outcomes in RID-SSISS training material based on the three taxonomies (Table 1).

| Level of training material | Learning outcomes | Bloom | SOLO | Fink |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational level | Raise awareness of ethical issues during the research process; | remember, understand | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge |

| Practice utilising the codes of conduct, being familiar with central topics; | understand, apply, analyse | relational, extended abstract | application, integration | |

| Learn together as a team, collaborate with peers. | evaluate | relational | human dimension, learning to learn, caring | |

| Advanced level | Develop one’s research ethics competencies by combining previous knowledge and implementing new tools; | understand, apply | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, learning to learn |

| Identify ethical issues by determining which ethical principle might be at stake.[1] | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | application, integration | |

| Utilise the ethical analysis steps to provide solutions to ethical dilemmas (in groups).[2] | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | unistructural, multistructural, relational, extended abstract | foundational knowledge, application, integration,

human dimension, caring, learning to learn | |

| Leadership level | Develop research ethics competencies by combining previous knowledge and implementing new tools; | understand, apply | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, learning to learn |

| Identify which ethical principles might be at stake in a case.[1] | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | application, integration | |

| Utilise the ethical analysis steps to provide solutions to ethical dilemmas.[2] | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | unistructural, multistructural, relational, extended abstract | foundational knowledge, application, integration,

human dimension, caring, learning to learn | |

| Implement different ethical approaches to the possible courses of action; | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, | |

| Take the role of a REI leader and display (some) REI leadership competencies during their group work. | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | relational, extended abstract | human dimension, caring, learning to learn |

Learning taxonomies are helpful not only in the design of learning goals for teaching, but also in devising appropriate targets of assessment. The coordination between learning goals or objectives, the methods used for teaching and the activities chosen to support learning, as well as the assessment of the learning are referred to as constructive alignment.[3][4][5] This means that the core components of a teaching should be geared towards supporting the same aim; namely learning. Learning taxonomies are helpful not only in the design of learning goals for teaching, but also in devising appropriate targets of assessment.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kitchener, K. S. (1985). Ethical principles and ethical decisions in student affairs. New Directions for Student Services, 30, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.37119853004

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mustajoki, A. S., & Mustajoki, H. (2017). A new approach to research ethics: Using guided dialogue to strengthen research communities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545318

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00138871

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Using Constructive Alignment in Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning Teaching for Quality Learning at University (3rd ed., pp. 50-63). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Remarks

What is this about?

Why is this important?

Learning is what the learner does, but it can be facilitated through what trainers do and through appropriate teaching activities.[1] The Taxonomy of Significant Learning (sometimes also referred as the Fink’s taxonomy) is not hierarchical in the same way as the other two, however, it builds on Blooms’ taxonomy by including a long-forgotten affective component into the discussion (namely caring).[2] It encourages to include into the learning outcomes the objectives foundational knowledge, application, integration, a human dimension, caring, and learning to acquire competencies, thus providing a holistic approach to learning.[2] However, since the existing material aligns with Bloom's and SOLO frameworks, this module will primarily describe these two to ensure coherence and consistency in training delivery. Nevertheless, we encourage trainers to also consider the more effective type of learning objectives proposed in the Taxonomy of Significant Learning.

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: an integrated approach to designing college courses (Revised and updated edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Use the Bloom’s taxonomy

Bloom's Taxonomy is a well-known educational framework that offers a methodical way to classify learning objectives according to cognitive difficulty. (e.g., Adams, 2015).[1] It is a hierarchical framework that uses cognitive complexity to classify learning objectives. Benjamin Bloom created it in the 1950s, and it is now a vital instrument in educational theory and practice. The taxonomy is divided into six stages: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating, and creating. The levels are arranged from lower to higher order cognitive skills. Fundamentally, remembering entails recollecting words, information, and fundamental ideas. Understanding is more than just remembering concepts; it also involves understanding meanings. Applying necessitates applying knowledge to novel contexts or problem-solving. Analysing means dissecting data into its constituent elements and identifying connections between them. Making decisions based on standards and criteria is the process of evaluating. Creating, in the end, involves coming up with original concepts and/or interpretations. The goal of applying Bloom's Taxonomy to training aims and results is to enhance comprehension by considering the knowledge, skills, and competencies that the specific training programmes were created to impart. The Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analysing, Evaluating, and Creating domains of Bloom's Taxonomy each reflect a different cognitive process and the depth and complexity of learning.

All taxonomic levels are relevant irrespective of the study or career level. However, the taxonomic levels may mean different things for different individuals. For example, application of knowledge may mean engaging with research designs, but senior researchers often use more complex designs than students still learning how to do research. Nevertheless, it is essential that the learning extends beyond remembering and understanding, and that the complexity of activities at all levels gradually grow as the individual gains experience, knowledge and confidence.

Remembering and understanding:

Here, the focus is on memorising key facts, concepts and theories relevant to the field of research and innovation. Understanding these foundational elements is critical to moving forward. For example, undergraduate students need to master the basic principles and terminology related to ethics and integrity to effectively navigate through more complex topics later. Similarly, individuals pursuing a PhD or who are new to academia need a solid understanding of basic concepts before they can conduct more in-depth analyses and applications, such as mastering the ethics of their own PhD research. Moreover, senior researchers may need to understand the basic concept of supervision and mentoring practices when it comes to supervising a team and PhD candidates.

Apply and analyse:

Learning should always be an active endeavour irrespective of career or studies applying and analysing knowledge. This is where the emphasis shifts to practical application and critical thinking. Early career researchers, junior professors and academics need competencies for applying the ethics and integrity concepts they have learnt to real-life scenarios in connection to conducting experiments, collecting data and critically analysing the results to gain meaningful insights. Through these activities, participants develop the skills necessary to contribute to the advancement of their field and address research questions with greater depth and sophistication. In terms of research ethics and integrity, this involves applying such knowledge and values to every step of the research.

Evaluate and create:

The highest level in Bloom’s Taxonomy involves evaluating existing knowledge and creating new knowledge. All researchers play a critical role in shaping the direction of research and innovation. They are responsible for assessing the validity and significance of research findings and identifying areas for further investigation and innovation. By synthesising existing knowledge and developing new ideas, theories or methods, researchers develop their field forward and inspire the next generation of researchers and innovators. All RE/RI training should include components, which encourage learners to extend their thinking to evaluation and creation. In practice, this involves having such a robust knowledge base and values so that even when encountering new ethical dilemmas or being posed with a novel potentially integrity-threatening situation, they can rely on having the ‘tools’ to handle the situation.

- ↑ Adams, N. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 103(3), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010

Use the SOLO taxonomy

Besides using Bloom’s Taxonomy to define learning objectives, the SOLO Taxonomy can be used .[1][2] The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome, or SOLO, is a way to set the learning outcomes according to how complicated they are.[1][2] In this way, the students' work can be assessed according to its quality and not according to how many parts they have understood correctly: initially, we learn one or a few aspects of the task (unistructural), then multiple aspects that are unrelated to each other (multistructural), then we learn how to integrate them into a whole (relational), and lastly, we can generalise that whole to still-untaught applications (extended abstract).

The SOLO taxonomy has been used to evaluate effectiveness of trainings as well as the development of ethical sensitivity and has been proven to be effective in the context of research ethics and integrity training.[3][4][5][6] The verbs emphasised in the descriptions below can be used as indicators of the appropriate levels in learning objectives.

Pre-structural level (0)

At the pre-structural level the learner fails to identify or approach topics in a meaningful way, but simply repeats the words in the question without understanding them.

Unistructural level (1)

At the unistructural level, the learner has sufficient knowledge to identify, recognise, count, find, label, match, name, and perform follow simple procedures. The learner identifies one relevant aspect displaying some familiarity with relevant concepts, but failing to outline multiple dimensions of it but failing to outline multiple dimensions of it. In the context of research ethics and integrity, this may mean identifying certain, perhaps common concepts, but having a limited view of them. For example, the learner may be able to identify some of the things that ought to be mentioned in an information letter to research participants but fails to understand all aspects of ensuring voluntary participation in research.

Multi-structural level (2)

At the multistructural level, the learner can enumerate, describe, illustrate, list, sequence, select, combine, and follow procedures, but struggles to make connections between concepts or draw conclusions based on interrelations. For example, the learner may understand that informed consent is necessary in research but fails to understand that this is so because of the need to respect people’s autonomy and right to make decisions that concern themselves.

Relational level (3)

At the relational level, the learner displays an ability to address the most relevant aspects of the concept and provide explanations pointing out interrelations and providing examples demonstrating their own reasoning. Corresponding action verbs include; analyse, apply, argue, compare, contrast, critique, explain causes, relate and justify. For example, the learner understands at least the main mechanisms and connections between FFP and the detrimental effects to science.

Extended abstract level (4)

At the extended abstract level, the coherent whole is generalised or re-conceptualised at a higher level of abstraction. The learner grasps a more abstract version of the concept, and recognises other domains to which the concept might be applied by displaying the ability to theorise, generate, generalise, hypothesise, create or reflect, formulate and reflect. For example, the learner is able to use knowledge about ethical analysis and ethical principles to solve a novel integrity-related dilemma, which the learner recognises is affecting a research group, but to which the learner has not been exposed before.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Using Constructive Alignment in Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning Teaching for Quality Learning at University (3rd ed., pp. 50-63). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- ↑ Löfström, E. (2012). Students’ ethical awareness and conceptions of Research Ethics. Ethics & Behavior, 22(5), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2012.679136

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., & Löfström, E. (2023). Learners’ self-assessment as a measure to evaluate the effectiveness of research ethics and integrity training: can we rely on self-reports? Ethics & Behavior, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2023.2266073

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., Löfström, E. & Rodríguez-Triana, M. J. (2022). Facilitating development of research ethics and integrity leadership competencies. International Journal of Educational Integrity, 18, 11, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-022-00102-3

- ↑ Tammeleht, A., Löfström, E., & Rajando, K. (Accepted 2024) Effectiveness of research ethics and integrity competence development – what do learning diaries tell us about learning? International Journal of Ethics Education.

Use The Taxonomy of Significant Learning

The taxonomy of Significant Learning or the Fink’s taxonomy is a non-hierarchical system that helps trainers devise learning outcomes to support deep learning. No dimension is considered more important than the other and within the course various aspects should be present.[1] Thus, this taxonomy provides an alternative frame for devising learning objectives for training. The fact that this taxonomy emphasises care and empathy makes it very suitable for training on ethics and integrity. The following is a short overview of the various dimensions:

Foundational knowledge

This dimension focuses on content knowledge and includes recalling and understanding of information and ideas.

Application

Here the learner demonstrates skills – they can be related to the use of knowledge or include skills necessary to interact in the subject, e.g. critical and creative thinking, decision-making, solving problems etc. For example, using the steps of ethical analysis to solve a situation involving an integrity-related challenge.

Integration

In this dimension the learner perceives connections between various ideas, disciplines, and experiences. It includes relating various ideas to each other, comparing, contrasting ideas and examples, and so on. For example, in solving an ethical issue, different ethical theoretical viewpoints may lead to diverse actions and solutions. Recognising how for example a virtue ethical approach may lead to a different solution than reasoning based on utilitarianism may be an expression of integration.

Human dimension

Learners learn with others, and they gain new understanding of themselves as well as others and alsoin the learning process. They recognise how people influence each other. Understanding how to respectfully work together for the greater good is an example of how the human dimension materialises positively in practice.

Caring

The caring dimension includes an affective stance and involves change in a learner. The learners start to see the reason to care about a topic, they gain new interests, feelings and values about the subject. Empathy and an ethics of care are values compatible with caring.

Learning to learn

In this dimension the learner understands that it is not only the outcome of learning that matters but also the process is important. This dimension includes guiding one’s learning for instance by inquiry, reflection and self-assessment. The role of reflection has been emphasised as a key activity in learning and individual development.[1]

Apply and Compare the Taxonomies

To illustrate how the taxonomies can be applied in creating learning objectives for training, we provide an example of an analysis of learning outcomes in RID-SSISS training material based on the three taxonomies (Table 1).

| Level of training material | Learning outcomes | Bloom | SOLO | Fink |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational level | Raise awareness of ethical issues during the research process; | remember, understand | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge |

| Practice utilising the codes of conduct, being familiar with central topics; | understand, apply, analyse | relational, extended abstract | application, integration | |

| Learn together as a team, collaborate with peers. | evaluate | relational | human dimension, learning to learn, caring | |

| Advanced level | Develop one’s research ethics competencies by combining previous knowledge and implementing new tools; | understand, apply | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, learning to learn |

| Identify ethical issues by determining which ethical principle might be at stake.[1] | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | application, integration | |

| Utilise the ethical analysis steps to provide solutions to ethical dilemmas (in groups).[2] | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | unistructural, multistructural, relational, extended abstract | foundational knowledge, application, integration,

human dimension, caring, learning to learn | |

| Leadership level | Develop research ethics competencies by combining previous knowledge and implementing new tools; | understand, apply | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, learning to learn |

| Identify which ethical principles might be at stake in a case.[1] | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | application, integration | |

| Utilise the ethical analysis steps to provide solutions to ethical dilemmas.[2] | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | unistructural, multistructural, relational, extended abstract | foundational knowledge, application, integration,

human dimension, caring, learning to learn | |

| Implement different ethical approaches to the possible courses of action; | analyse, evaluate | unistructural, multistructural, relational | foundational knowledge, application, integration, | |

| Take the role of a REI leader and display (some) REI leadership competencies during their group work. | apply, analyse, evaluate, create | relational, extended abstract | human dimension, caring, learning to learn |

Learning taxonomies are helpful not only in the design of learning goals for teaching, but also in devising appropriate targets of assessment. The coordination between learning goals or objectives, the methods used for teaching and the activities chosen to support learning, as well as the assessment of the learning are referred to as constructive alignment.[3][4][5] This means that the core components of a teaching should be geared towards supporting the same aim; namely learning. Learning taxonomies are helpful not only in the design of learning goals for teaching, but also in devising appropriate targets of assessment.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kitchener, K. S. (1985). Ethical principles and ethical decisions in student affairs. New Directions for Student Services, 30, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.37119853004

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mustajoki, A. S., & Mustajoki, H. (2017). A new approach to research ethics: Using guided dialogue to strengthen research communities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545318

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00138871

- ↑ Biggs, J. (1999). What the Student Does: teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development/Higher Education Research and Development, 18(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436990180105

- ↑ Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Using Constructive Alignment in Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning Teaching for Quality Learning at University (3rd ed., pp. 50-63). Maidenhead: Open University Press.