Evaluating the content of learning outputs

Evaluating the content of learning outputs

What is this about?

Even though analysing content of texts produced by learners as authentic learning outputs is time-consuming and difficult in case of large numbers of participants, it is possible to use deductive content or thematic analysis to extract specific topics.

We introduce some possible criteria for content/thematic analysis with examples. We will illustrate the criteria based on possible answers to the following case:

| Your research team is doing research involving preschool children. Part of your data collection scheme is to video record some planned activities during a regular day at the school. You have asked the children’s’ parents for informed consent. Slightly over half of the parents have consented, and you feel pretty good about your upcoming data collection. On the day of the activities and recording the children whose parents had not consented to their child participating in research had to be taken to another room for the duration of the data collection. You have planned that it like this because, it will be easier to set up the cameras and to manage the data if you have only those children in the room for whom the parents have given their consent. As you then, with the help of a preschool teacher, guide the remaining children out of the room, they begin to scream and some start to cry. They feel that they are being punished for something and that they will miss out on a fun activity that the others will do. |

|---|

Evaluate using ethical principles

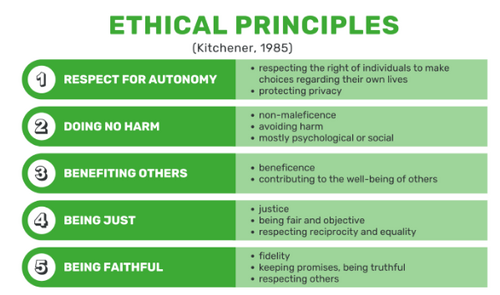

Ethical principles (Kitchener, 1985) can be used to evaluate the characteristics of the ethical dilemma:

Figure 1. Ethical principles (Kitchener, 1985).

In the case introduced in the section what is this about the following response may be given by the learners:

Ethical issues that could emerge in this case: underage children, parental consent, procedure of getting the consent, considering the wishes of the child, organising data collection, cooperation with the (pre)school, which is more harmful for the child - being recorded (for the research purposes) or being upset about the procedure of fulfilling the parent’s demands.

Ethical principles that can be at stake in this case:

- respect for autonomy - in this case there is a conflict between the autonomy of the child and the autonomy of the parent - for the researchers there is no simple answer. The procedure of informing should be altered to prevent these situations from happening in the future.

- doing no harm (non-maleficence) - in this case the researchers’ only chance of not harming the children whose parents had not given their consent would have been not proceeding with data collection, but in that case they would be harming the research/society/greater good.

- benefiting others (beneficence) - the research is probably important to the society, but it is not right to harm anyone to benefit others.

- being just (justice) - the researchers must be fair towards the children, their parents, the school, the society - if their rights get into a conflict of interest, new means of data collection must be found.

- being faithful (fidelity) - researchers must respect the wishes of the parents, but also children.

Evaluate using ethical analysis

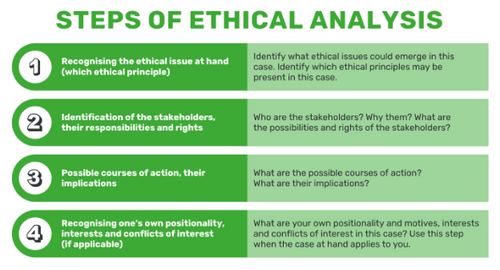

The ethical analysis framework (Mustajoki & Mustajoki, 2017.) is used as a tool for solving ethical dilemmas. The framework consists of the following steps:

Figure 2. Ethical analysis (Mustajoki & Mustajoki, 2017).

In the case introduced in the section what is this about the following response may be given by learners:

- Who are the stakeholders? Why them? What are the responsibilities and rights of the stakeholders?

A. Researchers - the team of researchers need data for their research, they have planned their activities and data management, they have the support from their leader and institution, they need the research to bring new knowledge into the society and also promote their own careers.

B. Children - research may often include children, they will also benefit from the research. By law, underage children (there are some differences of age in different countries) need a parental consent to be part of the research. At the same time, UN Article 12 states that the child’s opinion must be asked and considered (depending on their development). If the parent’s and child’s opinions contradict, the researchers cannot decide what to do, the best option might be to quit data collection and find new measures and plan the informing procedure better.

C. Parents - are responsible for their children, have the right to decide for their underage children, must consider the well-being of their children. Parents should be aware of the implication of their decision - whether their decision may harm the child (mentally), whether they are hindering the improvements in the society. Parent should seek for more information to consider all the alternatives.

D. (Pre)School - if the school allows the researchers conduct data collection in their institution, then the school leader should also be informed and evaluate the situation - either make suggestions on how better organise data collection and what the benefit is to the children/school.

E. Research institution - provide guidance, training to the researchers on how to better organise data collection, especially involving people/children. Maybe an ethics review is necessary or advice from the ethics committee.

F. Society - needs research for improvements, should encourage researchers conduct research to develop better policies. It is important to spread knowledge that all citizens can contribute to improvements by participating in surveys.

- What are the possible courses of action? What are their implications? -

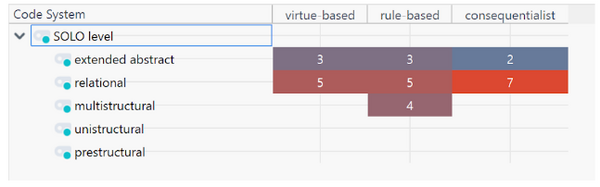

Using ethics theories to analyse learning

Theories of normative ethics can be used to analyse participants’ responses to a variety of learning tasks such as analyses of cases or essays, in which participants describe their own approaches to an ethical question or their thinking about ethical matters. If familiarity of ethical approaches or ethical theories are part of the course objectives or intended learning outcomes of the training, an analysis of how the learner has addressed these is very suitable.

For example, the analysis of authentic responses to learning tasks can involve the identification if deontology, virtue, utilitarian ethics, or other approaches, as relevant. The Virt2ue project materials on the Embassy of Good Science Preparatory Viewing: Introduction to Concepts & Themes (embassy.science) provides helpful guidance (e.g. a video) into understanding common ethics theories.

The analysis takes a bit of time but may yield interesting information about how learners have understood the concepts. The analysis can focus on the presence of the theoretical concepts in a text, the depth at which the learner uses the theoretical knowledge, or the levels of understanding that the learner displays regarding pertinent ethical theories or approaches. The depth of thinking, which the learner displays, can be analysed with a scheme of levels of reflection or the SOLO taxonomy / ECAG Grid.

Figure 3. Example from a case study analysis done by 7 people displaying ethical approaches (visual from MaxQDA programme).

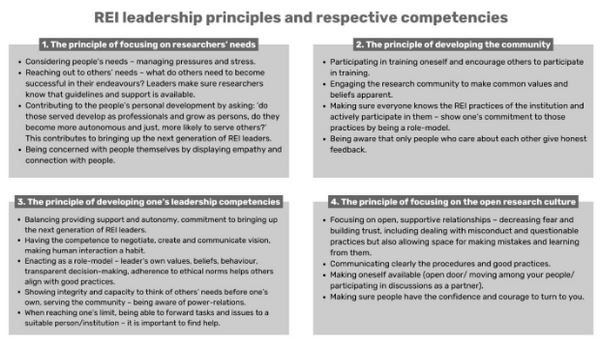

REI Leadership principles

REI leadership framework outlined in figure 4 (Tammeleht et al., 2022;Tammeleht et al., submitted) can be used to guide a meta-analysis of surveys or documents guiding the practices of REI.

Figure 4. REI leadership framework (improved version from Tammeleht et al., submitted)

The meta-analysis can be guided by the following template (figure 5) (from Tammeleht et al., submitted):

| Meta-analysis of a national research ethics/integrity survey

Country: Link to the national survey: REI leadership principle I: Researchers’ needs – what is perceived as a threat? What are the needs? … REI leadership principle II: Community – infrastructure: guidelines, trainings, RI advisors;supervision, team support … REI leadership principle III: Leaders’ competencies – from open answers/ any questions that pertain to leadership/administration … REI leadership principle IV: Open research culture – trust, courage – how do researchers perceive dealing with misconduct, how do they perceive support? |

|---|

Statistics and learning analytics

Statistic is an easy measure for counting answers and identified topics. Learning analytics tools (especially those designed into an application) usually calculate the averages and divisions of responses and display them in graphs. Statistics tools like MS Excel, Google sheets or even SPSS (not to mention R) could be used to analyse the collected numerical data.

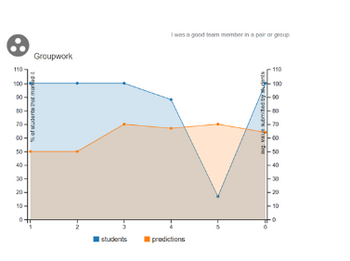

For example, ProLearning app creates ratios of students’ and teacher’s answers (figure 6):

Figure 6. Students’ and teacher’s answers to the same question asked in 6 training sessions.

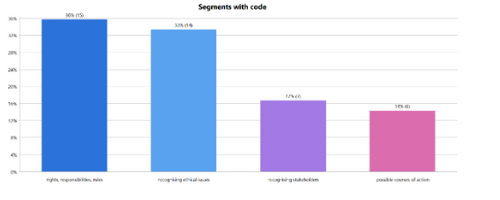

It is possible to count the answers given by learners (figure 7):

Figure 7. Responses to various ethical analysis steps.

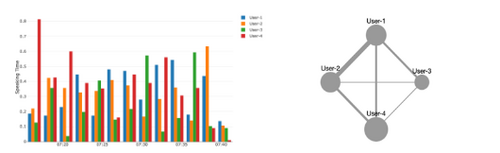

Even group dynamics can be displayed by counting the turn-taking of learners (as done by CoTrack app) (figure 8):

Figure 8. Turn-taking of four learners (right) and the corresponding group dynamics display (left) (from Tammeleht et al., 2022).

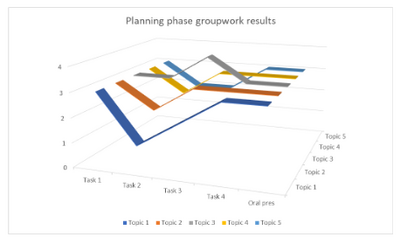

In addition, the learning process can be displayed on a graph to illustrate the development of understanding (SOLO levels 0-4) (figure 9):

Figure 9. Development of 5 topics during 4 group-tasks and an oral presentation. SectionRemarks

Authors: Erika Löfström, Anu Tammeleht, Simo Kyllönen,

This course was produced on behalf of the BEYOND project. The BEYOND project was finded by the European Union uder the grat agreement n. 101094714